This needs a preamble. In 1981, I attempted a circumnavigation of the Mediterranean by ferry. In 1976, with my first wife, I had travelled, by Turkish Maritime Line ferry from Barcelona to Piraeus stopping at Marseilles, Genoa, and Naples and then having crossed to Turkey by island hopping, from Fethiye to Antalya.

We said we would come back and do the complete trip, which was then possible, along the East coast of the Mediterranean and along the north coast of Africa back up to Barcelona.

My first wife and I parted, and I vowed to do the trip alone, and to write a book about it which I would call An Absurdly Small Sea, a quote from Lawrence Durrell’s Justine

In the intervening years, the Turkish government had sold the ferry line. Which made it very difficult to complete what we had started. Apart from that, Lebanon was at war.

I tried very hard, but did not complete the trip, which I attempted in one big bite, unlike Eric Newby, who completed the trip in small bites for his wonderful book On The Shores of the Mediterranean. Apart from anything else, I was exhausted by solitary travel.

My book was to be a combination of travel journal and fiction inspired by travel. I have always written prolifically when travelling. And although i didn’t finish the book, I have mined it for some years for stories. This is one I have just transcribed. At the time also, I was getting bored with my life as an advertising writer. That is the background.

He couldn’t believe it. He walked out of his hotel on the Piazza Pantheon and they were shooting a TV commercial. He sat at the café and ordered a Punt e Mes: when in Rome. At first he thought of walking up to the producer, handing him a card and making himself known. But then, as he watched them, he began to laugh. Softly at first, and then almost hysterically, clutching himself, trying to be make an exhibition of himself.

There were two huge and unattractive drag queens to his left, heavily powdered and blue-bearded. They stared at him coldly, sniffed at the sky and turned their broad chiffon covered backs to him. An English family at another table, staying in one room of a pensione, sharing an ice cream, all eight of them, looked at him embarrassedly, and also looked away.

But he couldn’t help himself. From his distance, it all looked so absurd, a parody. There were the models, fresh and empty of face, perched on the side of the fountain, primping. There was the director, a large man with a lascivious mouth and greasy lips, yelling orders, snapping his fingers, strutting up and down the piazza, stop watch in hand. There was the sad old grip in the hounds tooth check cloth cap throwing breadcrumbs at the pigeons to flurry them on cue. The agency producer in his linen suit and clipboard, brow furrowed, making notes, the makeup girl with a box of tissues gossiping with the stylist. The cameraman squinting through the view finder of the Arri 35 on a high hat. A little fellow in a beanie (the client?) kept racing up to the models and handing them – biscuits? wafers? – like a priest conducting communion. He saw cruelty, self-satisfaction on the faces. The director wishing he was Fellini. The cameraman wishing he was on a feature. The producer wishing it was all over. He felt his life grip him like a giant steel spring.

The grim laughter and scorn turned in on him, a death fear squeezed cold sweat from him. Flying in the day before, gazing out of the porthole, how easy it would have been to smash the plastic and be sucked out in to cold space, being squashed on the way by the silver wing (‘no step’ written across it). Sitting in his room with a fifth of Jack Daniels, how easy to swig the lot and die.

As he left the hotel room they were shooting a television commercial in the piazza. But it wouldn’t die. A bearded man in a black and white cap pumped the contents of a Smith and Wesson automatic into it. It lay beneath the fountain, flickering dimly, sending out its message, jingling and jangling. A tall gaunt man stepped out of the gawking crowd and pulled a long dagger from beneath his black overcoat and stabbed it in the pack shot. It faltered but still wouldn’t die. The crowd was angry.

“Die you bastard!”

“Shoot it again”

There was no sympathy. Nobody cared. Suddenly, it began to roll down the piazza, past Fiorucci, past the gelataria, the crowd followed, cursing, screaming and kicking at the commercial, belting it with rolled up copies of Corriere della Serra and La Republica, jabbing it with umbrellas and throwing bottles at it. A Carabiniere unslung his machine gun and emptied it into the cringing commercial.

This time it looked like the end. It gave a last ghostly flicker, a last sputter of voice over and faded to black.

The crowd went wild. They danced they cheered they sand and the made love indiscriminately, falling to the pavement, stranger with stranger, dog with cat. The revelry went on well into the night, gathering strength. As people let, more arrived, joining in the frenzied dancing over the dead body of the last television commercial.

Towards morning as the first pale rays of dawn wrapped around the dome of the Pantheon, the party began to break up. Footsteps echoed down the Via Pantheon, hoarse voice joined in bedraggled song until finally, the body was left lying, cold and trampled in the gutter.

He stood quietly in the doorway of the Hotel Sole, hands deep in his pockets, staring down at it. It glowed, pale and phosphorescent in the rose light of the Roman morning.

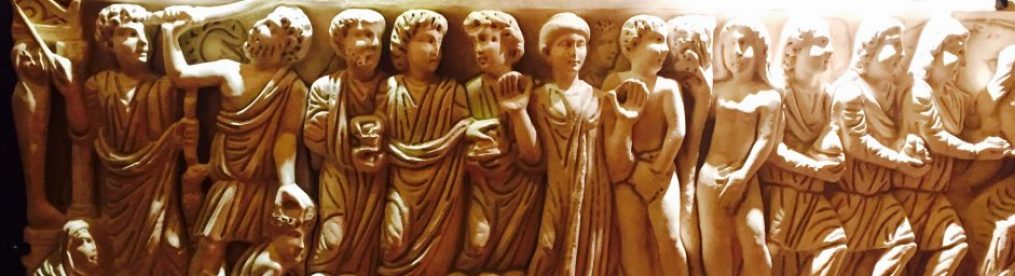

And then came from inside the Pantheon the sound of muffled drums. The giant doors creaked slowly open to reveal harlequin, mouth drooped in sadness like a hanging quarter moon leading a long procession, followed by a little drummer boy dressed in a doublet and hose.

Slowly, with measured steps, the procession marched across the Piazza and past the dead body of the last commercial.

They were all there. All the greats, all the near misses. Behind harlequin was J Walter Thompson with his grey beard and yachting cap. A dumpy Leo Burnett squinting through his horn rimmed spectacles, holding a bowl of apples. There was the Jolly green giant, Chesty bond, the Marlboro Man with a hacking cough on the back of a large brown horse. The Esso tiger padded softly along, the Whitmont Man wiped a tear from beneath his patch.

As they passed the pale shadow of the body, they gave a thumps or paws up, and faded slowly away.

He stood silently, watching the procession, recognising each ghost as they walked, marched or shuffled past. Finally the doors of the Pantheon groaned shut. The procession was finished. The carnival was over.

He walked over to the boy, picked it gently up, and dropped it in the fountain. It sank without a trace.

He waked back into the hotel. The student of spettacolo handed him his key with a wry grin. He slept well for the first time for a long time.