How can a bowl of rice gives us an insight into the past – and offer hope for the future? Let’s have a look at the history of paella, the rice dish that, for most people, says Spanish food. And in ways that many hadn’t even thought of, they’re right.

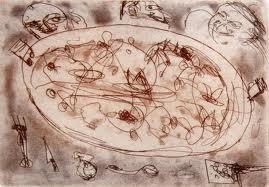

Paella is a dish named after the pan in which it is cooked, the paellera. In its purest form, it consists of rice and vegetables. Without the rice, it is very like another more ancient dish which did not contain rice, a dish called adafina. But let Spanish food historian Clara Maria de Amezua tell us about it.

“Adafina is an ancient Sephardic (Spanish Jewish) dish: the origin of the name is Arabic and applied to both the food itself and the receptacle in which it is made, much like the modern day paella.”

The Jews were in Spain as far back as the early Roman Empire. Some Judaic traditions have them there even earlier, from the destruction of the Kingdom of Judea in 587 B.C. and the fleeing of the tribes of Benjamin and Judah to Sefarad, the Jewish name for Spain.

But adafina was a meat and vegetable dish, and contained no rice, because there was no rice in Spain when the Jews arrived. The Arabs bought the rice.

The Arabs arrived in 711 A.D, and proceeded to place Moorish Spain at the centre of the civilised and cultured world. They travelled, explored, invented, and brought back from distant lands new plants and methods of cooking. From Ethiopia, for example, they brought back Triticum durum, hard wheat, and, according to a theory (hard to prove or disprove) of food historian Clifford Wright, invented pasta as we know it today, because the pasta made with Triticum durum can be dried, to form what Italians call pasta asciutta. From India and the far east, they imported rice, and planted it in the deltas along the Levante, that region of Mediterranean coastal Spain which runs roughly from Castellon to Alicante, whose centre is Valencia. And it is from Valencia that we get Paella.

But before we go to Valencia, let’s spend a little time in Moorish Spain. Especially between 711 and 1000 under the Umayyad Dynasty, Jew and Muslim lived side by side in, if not harmony, at least relative peace, a period called the Convivencia. Indeed the Jews contributed enormously to the magnificence of Moorish Spain, both intellectually, artistically and in government. So the question we must ask, especially of current Middle Eastern leaders is this: if it happened then, could it happen again? So you see that we can find both history and hope in a simple bowl of rice.

The complete name for the paella of Valencia is paella valenciana de la huerta – meaning from the vegetable garden. Paella (the dish) was a product of rice and vegetable cultivation, and, for meat, included whatever was on hand – but not seafood, which came from the coast, was not easily transportable and was, for inland dwelling peasants, expensive.

Instead, it might include snails, chicken, rabbit, or eel. There are rice and seafood dishes (Spanish cuisine includes well over one hundred rice dishes) but they are not paellas. For the very strictest interpretation of paella by a gastronomic pedant, listen to the Spanish novelist Manuel Vasquez Montalban’s creation, the gourmand detective Pepe Carvalho:

“I made myself quite clear. Half a kilo of rice, half a chicken, a quarter-kilo of pork shoulder, a quarter kilo of peas, two peppers, two tomatoes, parsley, saffron, salt and nothing else. Anything else is superfluous.”

In the same book as the above, Montalban also quotes José María Pemán’s marvellous ‘Ode to Paella’, which illustrates both the Spanish passion for food and contempt for rules: Carvalho’s own precepts for paella are countermanded in this poem:

O noble symphony of colours!

O illustrious paella!

O polychromatic dish

eaten by the eyes before touching the tongue!

Array of glories where all is blended.

Divine compromise between chicken and clam.

O contradictory dish

both individual and collective

O exquisite dish

where all is fair

where all tastes are as distinct

as the colours of the rainbow!

O liberal dish where a grain is a grain

as a citizen to the suffrage!)

And Señor Carvalho himself left out a most important ingredient: the beans – but he got the spirit right. I tasted my first such paella at a little restaurant called the Gallo d’Oro near the exquisite central markets of Valencia and it was only then that I understood what all the fuss was about. Although many will tell you paella should be cooked outside, over a wood fire – and only by men.

An interesting development in the history of this dish is that now, officially, only ten ingredients are allowed: olive oil, rice, chicken, rabbit, ferraura and garrofó beans (specific to Valencia), tomato, water, salt, saffron and rice. Dispensation is given for the addition of duck, snails and artichokes as regional variations. This was as a result of a recipe submitted in 2012 to the Conselleria of Agriculture in Valencia by the restaurateur Rafael Vidal. His recipe was granted the status of ‘paella valenciana tradicional con Denominación de Origen Arroz de Valencia’ – a Denomination of Origin.

But people will eat what they like, as they should, and as should you. If you want to put Balmain bugs or witchetty grubs into your paella, the food police will not arrest you. My neighbours in the little Spanish village in which I lived for some time prepare paella every Sunday – with seafood. And I guess, being Spanish, they know more than do I.

But for those of you who relish the authentic (Barbara Kafka’s “spectrum around an idea that changes even while we’re trying to appreciate it”) here is the most authentic recipe I could find, adjusted for local (Australian) conditions. Once you understand the spirit of the dish, your own additions will only improve it.

PAELLA VALENCIANA DE LA HUERTA.

Serves 4

INGREDIENTS

1 enamelled paellera (most important)

100g lima beans (fresh and newly shelled best)

100g cannelini or flageolet (ditto)

100 ml olive oil

salt

400g organic chicken cut into pieces

350g rabbit, cut into pieces

125g green beans, cut into pieces

100g tomatoes, skinned, de-seeded and finely chopped

16 cleaned snails in their shells or a sprig of rosemary

2 strands saffron

1tblspn paprika (Spanish pimentón is best, and that called la vera the best of all))

1.75 litres chicken stock

350g la bomba rice (the finest Spanish rice, calaspara if you can’t get it)

METHOD

Unless you are using fresh beans, soak the lima beans and butter beans overnight in cold water, then drain and rinse.

Heat the oil in a 40 cm paellera with a little salt. When it is hot, add the chicken and rabbit and fry over a low heat until golden brown.

Add the green beans and fry for 5 minutes, then add the tomatoes and fry for 3 minutes.

Meanwhile boil the snails in a separate pan for 5 minutes, then drain.

Crush the saffron then dissolve it in a little boiling water.

Add the pimentón to the paella, quickly add the stock and bring to boil. The quantity of stock is difficult to specify and may need a little practice. Add the rest of the beans. When boiling, add the snails rosemary and saffron and a pinch of salt and simmer for 30 minutes

Sprinkle in the rice and boil over a high heat for 5 minutes, then gradually turn down the heat and simmer for about 10 minutes until the rice is cooked and the liquid has evaporated.

Do not stir. If you have cooked the paella properly, you will end up with a brown, toasty caramelised circle of rice at the bottom of the paellera in the middle. This is called the socarrat, and is given to the most honoured guest.